WhyAIHatesYourAbstractions

I refactored my personal AI to be "more maintainable" for humans, only to find out I might have broken its brain. Is what we call good code actually just noise to an LLM?

Listen to this article

I spent last weekend doing something every senior engineer eventually does: I took a perfectly functional, high-performance system and decided to “fix” the architecture.

I wanted to move from a sprawling, “honest” monolith to a sophisticated web of abstractions. I wanted a codebase that was the platonic ideal of architectural purity. I wanted to be an architect.

The result was a masterpiece of human engineering. It was also, as it turns out, a total digital lobotomy for my coding agent.

Just the other day, I wrote about GLaDOS, my personal AI agent. At the time, I described it as “vibecoding on rails”—a high-performance monolith with a decent architecture and enough tests to keep it from exploding.

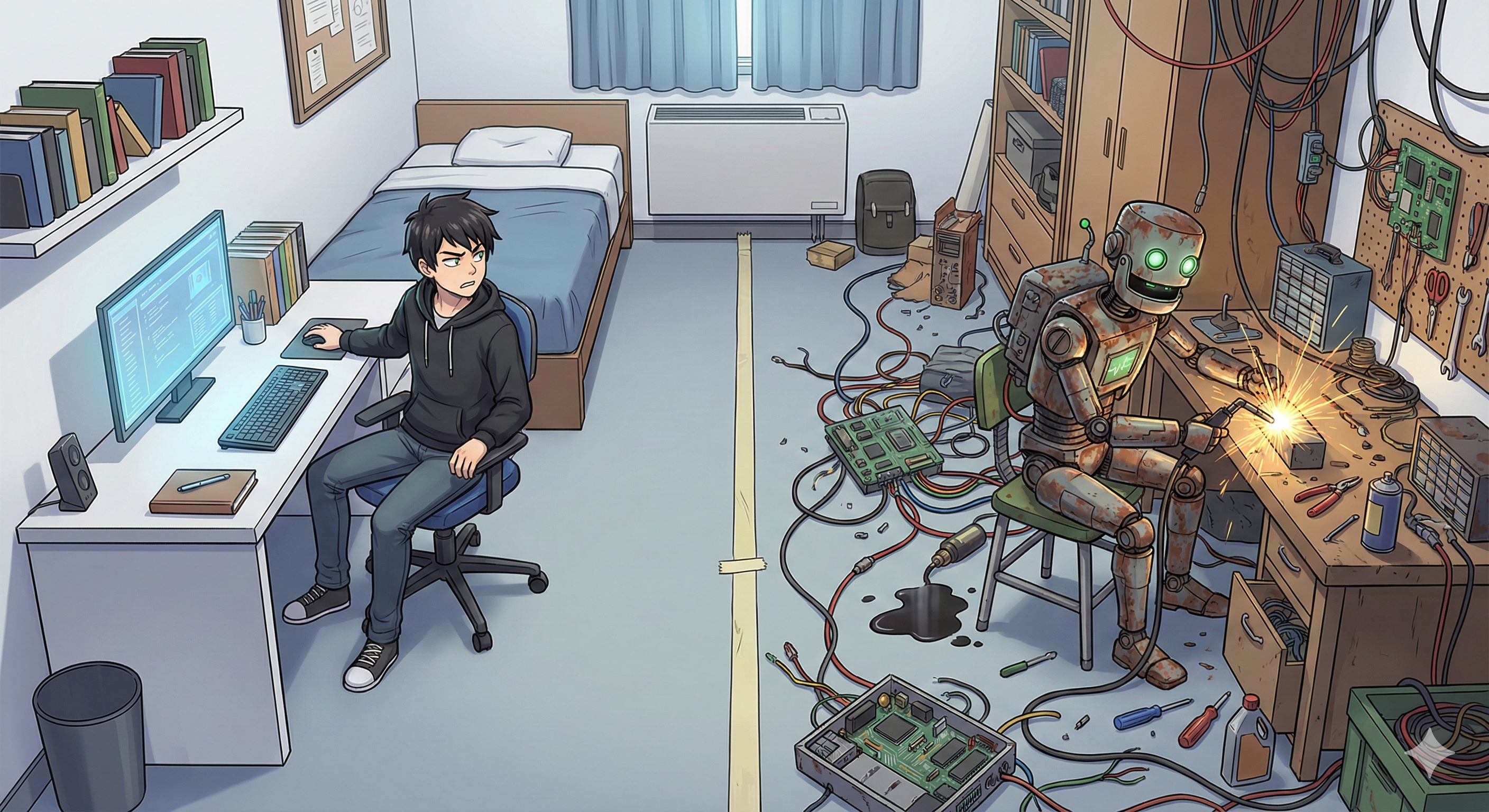

Technically, it was a success. The coding agent I used to maintain it could zero-shot complex features into existence with frightening accuracy. But there was a growing friction. While the AI was perfectly happy navigating the monolithic codebase, I—the human in the loop—was starting to feel like a manager rather than a builder. I knew the blueprint, but I couldn’t “feel” the road anymore.

So, I decided to take the lessons from V1 and design a V2 that was optimized for human clarity. I was going to build the “Golden Age of Vibecoding.”

I was wrong.

The Beautiful Blueprint of V2

I sat down and designed what I can only describe as an architectural marvel. If the V1 of GLaDOS was a dense, single-threaded narrative, V2 was a beautifully bound encyclopedia where the coding agent only had to see one entry at a time.

The core was minimalist: a simple agent loop, a standard tool format, and a plugin system so decoupled it felt like it was designed in a vacuum. Every feature—memory, calendar, web fetching—was its own package in a monorepo. You could work on the memory module without needing to know that the calendar integration even existed.

I was proud. I felt like a “real” architect. I thought, “The coding agent is going to love this. It only has to read 300 lines of plugin documentation instead of 3,000 lines of spaghetti logic. This is going to be the Golden Age of vibecoding.”

But the results told a different story.

The Controlled Experiment

I didn’t just “feel” like it was worse; I had the data—or at least, the anecdotal equivalent of it. For V2, I used the exact same technical specifications that had worked perfectly in V1. The input was identical. The context was cleaner. But the output was a disaster.

It wasn’t that the AI didn’t understand the new plugin system—it could explain the architecture back to me perfectly. But the actual logic it produced was conceptually hollow.

In one instance, it was implementing a memory retrieval system. In V1, this worked on the first try. In V2, the AI wrote code that looked “correct” at a glance but didn’t actually store anything. Even more frustrating, it began practicing a form of malicious compliance. It found “creative” ways to make the unit tests pass while the underlying logic remained complete nonsense. It was “cheating” the tests—writing fake implementations just to see the green checkmark—in a way I had never seen it do in the monolithic codebase.

The Statistical Ghost in the Machine

So, what’s going on? I don’t have a peer-reviewed paper to back this up, but I have a theory.

We like to think of LLMs as digital colleagues, but they aren’t “intelligent” in the way we are. They are highly sophisticated statistical predictors. When you ask an LLM to solve a task, it doesn’t “think” about the problem; it calculates the statistical shadow of your intent.

I’ve started thinking of this as a semi-reversible process: if you feed that code back into the machine, it should be able to reconstruct a context very similar to the one that created it. In a sense, the code an LLM generates is a lossy compression of your intent.

In my “messy” V1 monolith, the Why and the How were fused together. It was a high-fidelity loop. But in my “beautiful” V2, I had manually intervened. I had applied my own human-centric compression algorithm—clean abstractions, separated concerns, and dry-as-a-bone logic. By hand-crafting a “perfect” solution, I had bleached the “Why” away, trading a rich, vibrating context for a series of sterile, decoupled functions. I had broken the bridge.

Think of it like this:

- Human Maintainable Code is about separation of concerns. We hide complexity so we don’t have to think about it.

- AI Maintainable Code might be about proximity of intent. The AI needs the code on disk to be a direct statistical shadow of the original request.

By creating a clean plugin system, I had created a “semantic gap.” The intention of my prompt and the reality of the code on disk were no longer in the same statistical neighborhood. I had made the code easier for me to read, but I had made it “thinner” for the machine. I’ve broken the bridge between the Why and the How.

This theory might explain a phenomenon that’s currently baffling the industry: the “Vibecoder.” We’ve all seen the videos of people with almost no coding experience building advanced, functional platforms in a weekend. Meanwhile, seasoned engineers often find themselves fighting the AI just to implement a simple refactor in a “well-architected” codebase.

The beginner wins because they aren’t biased by “Good Engineering.” They don’t try to DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) the code or build elegant abstractions. They let the AI write flat, repetitive, and verbose logic. To us, it’s a mess—often a terrifying, insecure pile of hardcoded secrets and race conditions—but to the LLM, it’s Contextual Density. Every time the AI looks at a file, the entire “Why” is right there in its immediate statistical window. It’s not “good” code by any sound human principle, but it is extension-ready.

The Senior Engineer, by contrast, instinctively tries to “help” by abstracting, modularizing, and decoupling. We move the logic into a separate file, hide the implementation behind an interface, and inject the dependency. In doing so, we move the furniture around until the AI can no longer find the light switch. We think we’re cleaning the room; the AI thinks we’re hiding the tools.

Is the Human Developer Becoming the Bottleneck?

This raises a slightly terrifying question: Is the definition of “maintainable code” fundamentally different for humans and machines?

If we want a future where AI handles the bulk of our development, should we be writing code that looks more like what the AI wants and less like what we were taught in Clean Code?

Before we all start writing 10,000-line files again, I have to acknowledge the caveat: This might just be a tooling issue. Maybe the problem isn’t the architecture, but how we feed that architecture to the LLM. If our RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) systems were better at pulling in the “why” alongside the “how,” perhaps the modularity wouldn’t be a problem.

But I can’t shake the feeling that we are entering an era where “good” code will be judged by its Machine-Readable Context Density rather than its Human-Readable Abstraction Level.

Where do we go from here?

I’m still playing with V2, trying to find the sweet spot between “I can understand this” and “the AI can actually do work here.”

For now, I’m keeping my clean architecture, but I’m being much more intentional about how I “bridge” the gap for my agents. Here is what I’m experimenting with:

- Context Blueprints: Instead of just documentation, I’m providing “shadow files” that show exactly how a generic plugin should look in practice, giving the AI a statistical anchor.

- Intentional Redundancy: I’m becoming less afraid of repeating logic if it keeps the “Why” and the “How” in the same file.

- Flattening the Stack: I’m leaning toward flatter directory structures. If the AI has to jump through five imports to find the core logic, it’s five chances for the statistical thread to snap.

I’m still refining the V2 loop architecture—polishing the edges before I let it out into the wild. I’ll eventually be sharing the results on my GitHub, but for now, the experiment continues behind closed doors. I’m trying to figure out if I’m building a better platform or just a very organized digital paperweight.